Tie Three, So Shall It Be, The Ilam Campus Gallery, Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha University of Canterbury, February 19th 2025

Extracts (smoke rising) from a talk given on form and perception in Tie One, The Spell’s Begun – the first in an ongoing work based on a nine-knot spell – at the Suter Art Gallery Te Aratoi o Whakatū on 22 June 2024. Barbara Garrie asked questions of the artist and of Carl Mika, who also read from new writing on āhua, hinengaro, wā and wai.

This time of year is a potent time for my work, when distractions are quietened so I can listen to what’s going on below the earth, hear the essence. It’s not only regenerative, but generative. Today is powerful with a full moon, and Matariki is with us – Yule and Winter Solstice.

Behind you is a veil, made using smoke photographed from a saining ritual, a Celtic tradition for protecting, blessing or consecrating. I combined this with found internet smoke, digitally drawn smoke and printed it on fabric for these long protective drops to walk through.

There is a scent also hanging in the room, made with Erihapeti McPherson. Erihapeti often hypnotises me, so we are accustomed to rolling around in my subconscious together. This scent was created through hypnosis, with ‘a moment of reverence’ as our provocation. I answered a series of questions, each correlated with rākau, essential oils and flower essences, which were blended to form the scent. We intentionally chose not to document the process, ensuring it can never be recreated.

The gallery’s interior architecture was built according to the golden ratio, which gives a sensibility to the proportions, and accounts for its special atmosphere. I’ve taken its arch shape for the fairy doors that appear in the show, made for the fae in the gardens outside. I wished to honour folklore’s unseen non-human entities that are linked to the natural world. The green paint colour points to the Victoria Gardens next door, tended for a dead queen in this colonised country.

I think about notions of spirit through what I’ve come to know as technologies of intuition – noticing how I make things, knowing through making, getting comfortable with not understanding these things until they’re made.

I had made a lot of work leading up to a show, sitting in the studio, surrounded – I was unsure about what was happening. I realised this dark fabric that had gathered was Queen Victoria in my studio, and the cult of mourning that she inspired, celebrating death for half her long life – the wearing of black, keeping a lock of hair of someone who died, types of lore that links us to another realm.

The witch balls here are based on objects used in 18th century Britain and Europe for both repelling and attracting evil. They were hung in people’s corners, high up in living areas, or in windows, to tell evil to go away, or to call it in to trap it inside the ball. They were first documented in the 14th century as lo-fi mirrored-glass security technology for shops and children’s bedrooms. Four hundred years later, they were co-opted into magical practice, and now, adorn our Christmas trees.

Wherever there are fairies, there are mushrooms and what grows underneath. Their mycelium goes for acres and acres, and they all talk to each other through it – the collective consciousness of mushrooms. These cast mushrooms were originally intended for a work that was in the grass, but they don’t want to be in the earth. They want to be flying high above us.

This is, in a sense, a representation of a living studio space – in my head, in another realm, in my actual studio – that pulls everything in and reminds us that we’re all coming from the divine mess.

The dark psychopomp sculpture is inspired by Carl Jung’s idea of a guide that can transport us from one realm to the next. It’s described elsewhere as a death-walker, someone that helps you die, or to transition from one space to another – a companion when passing over or through. In my art practice, everything seems to be collaborative. At times that’s making-thinking or other hands, and sometimes that’s with higher thought.

What you said about nowness and what congeals from it is very beautiful and potent to me.

It is an idea that came about as a response to notions of time and space through the translation of the term wā. Anyone who’s familiar with the modern language might know that wā is often translated as time and space. And immediately, when you introduce the vernacular of time, you automatically introduce a sense of linearity, that there is a past and a present and a future. You can’t avoid that with the jargon of time. I thought that there is a notion of presence – which is time-related discourse – and if we focus just on that and take away the idea that there is such a thing as time, then that might be closer to what we understand as things and people being totally interconnected; because they are actually now, and in being so, they don’t have a past, they don’t have a future.

What we might think of as past and future are just other instances of nowness. Things have a complete nowness, and things come to be. They manifest on the basis that the All has congealed in a particular sense, including in forms. So that’s where form comes to be. Something has a form on the basis that wā has enabled it through its intense nowness.

When I think of that in relation to art, there’s this potency of a moment, which is an ultimate presence of that form within the making. I always visualise that as a stacking up of everything that’s been experienced all at once, right now in one moment, congealing in time, that can give form to a potent moment. The divine mess remains – it is omnipresent. So even though there might be a work hanging in the gallery in isolation, it is always calling back to the Divine Mess, threading into that…

Do you findthat with the work you’re making, if we are trying to be counter-colonial and oppose this notion of time, then we also have to deal with the language that goes behind something coming first, a primordial ground? Do you find that there is a spiritual greatness that operates and gives rise to a battle going on with…[JA1] [JA2]

…the material realm of deadlines and being able to be transportable. What caught me was the idea of the All marvelling at its magnificence, the reflection of that magnificence and forming…

That’s assuming that the All does have some sort of appreciation of an aesthetic, and that we perform in some small way. And everything does, not just human beings, but all things – for the All. The danger with saying that is that you’re attributing human things, characteristics, to the All, and the awesome thing becomes an extension of ourselves, and that’s always a problem.

I think that’s pretty human.

With the mountain example I gave [of Te Heuheu’s successful claim to the Māori Land Court based on indicating that the eruption of Tongariro as ancestor affirmed his people’s occupation of the land] the mountain might have been finding the whole thing quite funny. Its eruption might have been because you guys are just a joke. You human beings… Te Heuheu might have thought that, oh yeah, this is supporting my arguments as I lay claim to this land. And it may have been, and there may have been more than one purpose for the showiness of the All. It may have been that the All was not noticing what was going on as far as human beings are concerned. It’s a possibility that the All might also be able to aesthetically appreciate anything, not just us.

As far as where thought comes from… The All regulates itself and configures itself in a particular way, and that now we have what we now call thought. Thought is whakaaro, and if you look at a number of genealogies, you’ll see whakaaro as an ancestor. I don’t think whakaaro is a good translation for thought – like a lot of things that don’t work, they just don’t fit over the top. But if it’s like and ego, or if it’s divine, then we are almost vessels through it. I guess what we have maybe in some anatomical way is the ability to wield it or gather it, but that’s about it.

So, are they witches’ balls, or are they representing witches’ balls? I don’t care to name that. They arrive out of the divine mess. Which part of that divine mess is the cognitive decision to make the work? It’s the research that’s going on, and my felt, embodied experience of being in the studio. Out of that comes the decision, through intuitive technologies, which has its own method and a way of arriving.

I follow intuitive thought, which you could liken to a trance-like state, or an unquestioning of what appears. And when I’m in that, it just arrives effortlessly. I feel it’s not really my business to describe in mundane terms what it is that’s arrived out of the Divine Mess.

[Stephanie Oberg:] I am just checking my interpretation of some of what you said. As part of the All we can never know, we are caught in the struggle of negotiating our relationship with the All, our existence. So, are we just entertaining ourselves as everything we do justifies our being?

I like to think knowing things is a delusion, really. And in colonisation… If you look through 95% of Indigenous scholarship they talk about knowledge. I am not having a go at my Indigenous colleagues – even by naming knowledge, I still privilege it. There is the problem of the word itself, and then there is its proliferation in Indigenous thought, Now, everything is about knowledge. We have even coined a term for it. What it does is take away the idea of mystery, because what is referred to in that word is empirical knowledge. There is a trajectory in the West where it comes from, and there’s been an uptake of the concept and problem. So that means that there is very little room for mystery and uncertainty. You don’t really pick up much work these days and read about uncertainty in its own right.

So, some struggles are more entertaining than others, and you are allowed to be more entertained.

The idea of trying to know something is very entertaining.

Sometimes I think that there is no such thing as metaphor. That puts a distinction between the presence of an object and its representation, when it simply is. It’s not metaphorical. There’s no metaphorical…

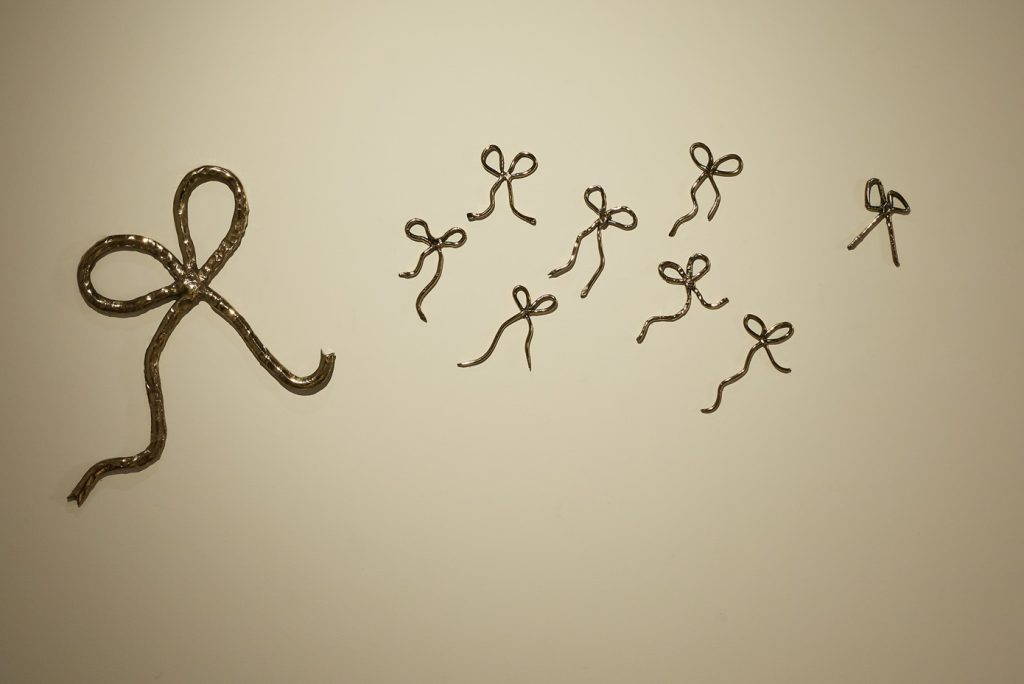

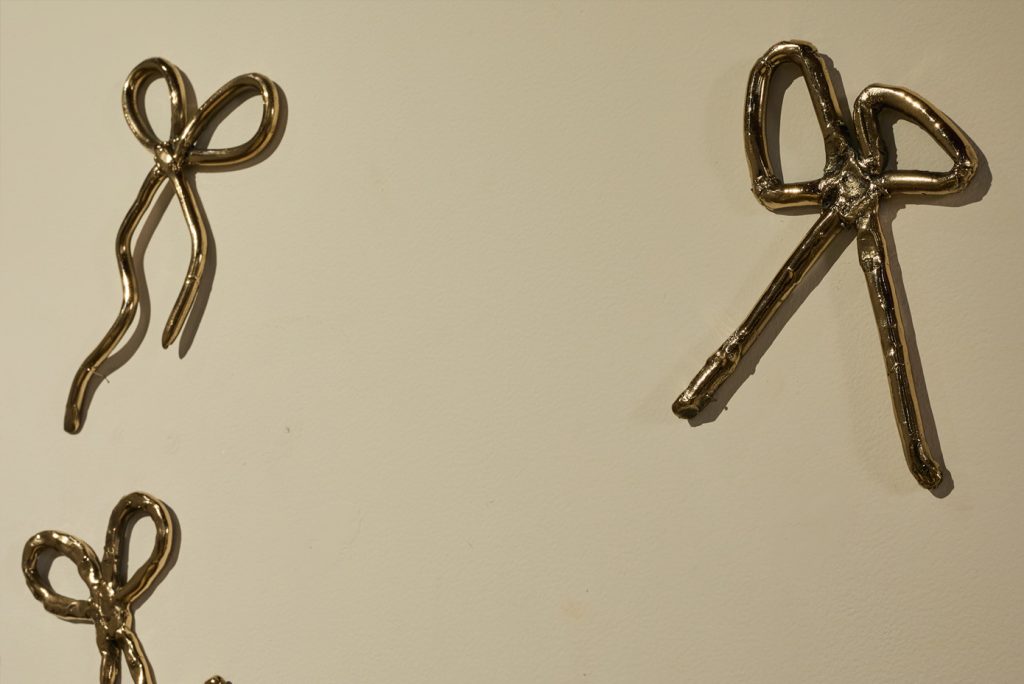

Tie one, the spell’s begun, the name of this work, has come from a very old spell. It’s the first line of a nine-knot spell to knot-in an intention or a wish. It’s a human impulse to knot, that wishing and wanting – intention and manifestation. And this relates to the work here – she’s got her nine bows tied.

I could describe these works as channels of intent. That’s as close as I can get to locking it down.

*This account of a conversation is based on notes taken by Dr Gwynneth Porter, an art writer and editor based in Ōtautahi Christchurch.

Sarah Rowlands Photography